Vaginal and Vulvar Cancer

Success Measurement

Strategic Initiative

Vulvar and vaginal cancers are considered the “forgotten woman’s cancers” and they represent 3-5% of all gynecological cancers. Advances in these two cancer types have lagged behind other cancers, possibly because of the rarity of these diseases. As the main treatment often involves surgery, it can leave a woman feeling as if they have lost their identity as a woman, severely impacting her quality of life.

Vulvar cancer forms on the outer lips of the external genitalia (or vulva). Vaginal cancer originates in the vagina, which is also known as the birth canal, and is approximately four times rarer than vulvar cancer. At both these sites, changes to cells of the vulva or vagina can lead to precancerous conditions. This means that the abnormal cells are not yet cancer, but there is a chance that they may become cancer if they aren’t treated. A cancerous (malignant) tumour is a group of cells that can grow into and destroy nearby tissue.

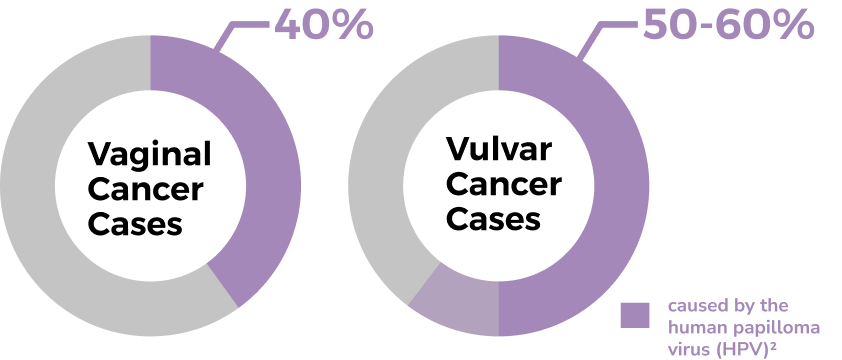

HPV-related vulvar and vaginal cancer often affect younger women but approximately 70% are over the age of 60. Vulvar cancer shares risk factors with cervical cancer, specifically the number of sexual partners, smoking and being immunocompromised. Non-HPV-associated vulvar cancers mostly affect women with a chronic condition known as vulvar dermatosis. Similarly, with vaginal cancer, in addition to HPV, risk factors include weakened immune system, smoking, if a woman’s mother took a medicine called diethylstilbestrol (DES) when she was pregnant between 1940 and 1971 and if radiation therapy had been previously done for cervical, vulva or anal cancer.

Until recently, vulvar cancers were treated as a single disease. New research, done in BC, definitively shows that HPV and non-HPV diseases are distinct conditions as they behave differently and have different treatment needs2,4. Non-HPV lesions are associated with more frequent recurrence and a higher risk of death. The data in BC suggests that aggressive surgery may be more important in HPV-independent lesions; the higher recurrence rate seen in recent years may be secondary to a change in surgical practice where less morbid surgical interventions had been favoured3. In addition, this team has demonstrated that HPV-independent lesions are less sensitive to radiation therapy. These results underpin the importance of disease stratification from the time of first diagnosis so that the correct surgery, adjuvant therapy, and surveillance schedule can be planned; this research provides one step in improving outcomes for women faced with a diagnosis of vulvar cancer.

The GCI recognizes that these two cancers are understudied. There is an opportunity to shift our understanding of vulvar and vaginal cancers by taking what we have learned from other gynecologic cancers and leveraging the technologies and approaches that we have developed to significantly impact outcomes for women with these rare cancer types.

This initiative will build on our preliminary studies of vulvar cancer and leverage the patient cohort we have compiled which is one of the largest cohorts of vulvar cancer patients linked to outcomes and HPV status currently available. Based on our previous work on the molecular stratification of ovarian and endometrial cancer, we propose to use a similar approach to better understand the etiology and pathogenesis of vulvar cancer with the goal of developing management strategies that are biologically-informed.

I. Prevention and Detection

Current screening methods for vulvar cancers include first a thorough clinical examination of the vulva and secondly if concern persists a biopsy is done and the histology (microscopic study) correctly interpreted. In precursor lesions that develop independent of HPV-infection; the histologic features are usually non-descript and they are often misdiagnosed or overlooked. As a result, a patient may be biopsied multiple times, before she is diagnosed as having a precancerous lesion. This is important because the window of opportunity for early surgical intervention and cure is often gone before the precancerous lesion is recognized. As this type of precancerous growth is a biologically aggressive lesion, early intervention is paramount if we are to prevent it from becoming cancerous.

To tackle this problem, we propose to catalogue the molecular features of both HPV-dependent and HPV-independent precancerous vulvar lesions using next generation sequencing technologies, with the hopes of finding a biomarker that could be used to accurately identify the premalignant growths. This would mean that women may be able to have their lesions treated before they turn into vulvar cancer.

The GCI will also play a role in raising awareness and educating both clinicians and women of the risks, preventative measures and symptoms of vulvar and vaginal cancers.

II. Diagnostics and Treatment

While the diagnosis of HPV-related tumours has been perfected over the years and there is little difficulty distinguishing between benign and cancerous forms of the disease, this is unfortunately not the case for HPV-independent cancers which are much more difficult to diagnose4. Also non-HPV related vulvar cancers tend to be more resistant to radiation therapy in comparison to its HPV-related counterparts. Of similar concern is the fact that getting the HPV vaccine will not protect women against non-HPV vulvar or vaginal cancers. With an aging population, the number of cases of non-HPV cancers are likely to climb in coming years.

All these factors combined, there is a clear need to develop better ancillary tests for early detection and diagnosis and more personalized treatment approaches for specific vulvar cancer types based on their unique molecular alterations. Molecular methods now allow scientists and clinicians to go beyond looking at tissue samples under a microscope. This lets patients benefit from heightened vigilance and closer follow-up, to prevent a missed diagnosis or recurrence of the disease. Our research is charting a course for improved diagnostics and treatments. This research could help shape clinical and diagnostic practices, as well as the transfer of knowledge at educational institutions and through medical textbooks. We are still in the discovery phase of this condition, and are working on coming up with uniform terminology and criteria in order to help clinicians and pathologists make more precise diagnoses

III. Survivorship

The survivor’s psychosocial outcomes of diagnosis and treatments of vaginal and vulva cancers can affect their quality of life and may require relationship adjustments8. Nearly 90% of survivors reported supportive care needs and if diagnosed with anxiety or PTSD, results in a four-fold increase in unmet needs. Vaginal and vulvar cancer and its treatments can result in body changes such as scars, skin changes, change in shape and appearance of the vagina and vulva, changes to body functions, and sexual problems.

Comprehensive and extended supportive care services are required to address anxiety and trauma responses and investigate strategies to meet ongoing needs in order to improve long-term psychosocial outcomes.